Taking some short time to follow up on these posts and think about how I’ve prepped games. Disclaimer that these are only my opinions as just a regular person, rather than some distinguished expert.

Other Posts in this Series

For context, here are some other posts in the same series:

- Weird Writer https://rolltodoubt.wordpress.com/2025/06/12/how-i-prep/

- Evil Scientist https://eldritchfields.blogspot.com/2025/06/how-i-prep.html

- Jenx https://gorgonbones.blogspot.com/2025/06/how-i-prep-my-games.html

- Macropter https://macropterus.bearblog.dev/prep/

- Idraluna Archives https://idraluna-archives.bearblog.dev/how-i-prep/

- Vivanter https://mediumsandmessages.bearblog.dev/how-i-prep/

- J.N. Sinombre https://madgods.bearblog.dev/how-i-prep-or-how-i-lose-my-mind-over-nothing/

- Ms. Quixotic https://msquixotic.bearblog.dev/how-i-prep-arden-vul-part-1-spreadsheets/

- Mr. Mann https://bluemountain.bearblog.dev/how-i-prep-new/

- Reptlbrain https://glaive-guisarme.blogspot.com/2025/06/how-i-prep-xyntillan-campaign.html

- Todd/Hexed Press https://hexed.press/prep/how-i-prep-part-one-pre-campaigning/2420/

- LootLootLore https://lootlootlore.blogspot.com/2025/06/prepping-and-my-beach-trip-campaigns.html

- Sultan’s Musings https://sultansmusings.bearblog.dev/how-i-prep-for-my-weekly-game/

- elmcat https://elmc.at/in-pursuit-of-prep-serenity/

- oldhawkeyes https://unturnedhovel.bearblog.dev/how-i-prep-investigations-and-sandboxes/

- Warren D https://icastlight.blogspot.com/2025/06/how-i-prep-weekly-ish-megadungeon.html

If I missed your post please let me know and I will add it here.

Preemptive Anti-Prep Polemic

Overall, I am not a huge proponent of extensive prep procedures or even lots of prep in general. Youtube in particular is filled with endless advice content aiming to assuage the fears of struggling GMs, and I don’t think that advice content is very beneficial for anyone. This is for a few main reasons.

Prepping Is Not Playing

Prep itself is not play. Too much focus on doing enough prep can actually limit the amount of time you have to play in games. It also puts more pressure on the games that you do a lot of prep for to go well, and it can feel crushing when (for entirely random reasons) the game doesn’t work out as you hoped.

My own first experience as a GM was when I starting running 5e games in 2016-2017, where I would spend about 10+ hours of prep per session. When sessions were inevitably canceled due to scheduling, I would often feel a huge sense of disappointment. Finally, after about 20 sessions (a half year of play), I discovered that the prep itself was becoming tiring, and that, somewhat randomly, the few sessions where I didn’t have time to prep were actually going much better. See my post below for some analysis of why:

The Ref is Just Another Player

Hyperfocus on prep tends to encourage overinflating the role of the Ref in determining whether everyone has a good time, whether the game goes well, and so on. It can encourage the idea that the Ref is putting on a show and that the participants are merely attendees. When you don’t prep or prep less, it almost forces the players to take more of an active role. Your role as a Ref then becomes more about providing some prompts and then asking questions, adjudicating the answers as needed.

Party because of my dissatisfaction with prep, I started getting more into PbtA and Dungeon World in 2018, realizing that there were styles of play that did not require extensive preparation and where other players could also be co-worldbuilders. However, since getting more into OSR games, which typically eschew collaborative world-building, I don’t tend to lean into this as much now.1 However, even in OSR games, in the few time I’ve introduced more limited aspects of player-contributed worldbuilding, the players have responded to the prompt positively in almost every case (see more on this at the end).

More Prep Rarely Improves the Game

Whether a game succeeds or fails rarely depends on the amount of prep. It mostly depends on a bunch of other things like the dynamics of the conversation and whether people vibe together or not. To use an analogy, RPGs are more like a folk music jam than a classical concert: success is more a matter of listening and riffing off of each other rather than following the direction of a conductor. In this sense, the distinctive role of Ref is more like playing the bass or drums–the goal is to keep people together and give them something to riff off of, more than it is to impress with your cool solo.

Hedging disclaimer: this assumes that you have done some of the basics, like read a module if using one, come up with a dungeon with some entries if it’s a dungeon game, or come up with some answers to core questions (who, what, how, why, when) if it’s a mystery game.

Emergent Prep is More Focused

You don’t know what your players are interested in, until you actually play the game. For example, you may spend a lot of time thinking about one particular village, only for players to steal something from the guard and then run to the next village over. You might come up with a whole alchemy subsystem, only for your players to be interested in necromancy instead.

You can mitigate this somewhat through clearly communicating the game’s pitch and boundaries–for example, in a megadungeon the shared expectation is that the game is primarily about delving the main dungeon. However, even within those bounds, there’s a huge about of variability when it comes to everything else. If the players have genuine choices, then they will inevitably focus on or come up with things that can’t be fully anticipated.

Polemic Summary

In general, I don’t think having good or bad prep practices is especially important, primarily because RPGs are a collaborative experience and so whether a game succeeds or not depends primarily on the table conversation and how it goes, rather than what the GM wrote down in their notebook.

As far as RPG advice, I think more thought should be aimed at how to facilitate productive conversations within games, although I don’t have great examples of this at the moment.

How I Prep Modules

Ok now for the boring part. When running a module, I typically start by reading the intro and then skimming everything else. I try to aim for no more than 1/3rd of the time prepping relative to the actual play time, so a 3 hour session of an unread module may require 1 hour of prep. For OSR dungeons following a standard format, this is more likely to be 30 minutes or less.

Disclaimer: Active versus Passive Prep

The timeframes above are based on “active prep,” that is, time spent specifically dedicated to nothing other than preparing for the game. Besides this, I do spend a lot of time in passive prep, that is casually thinking about some stuff that might improve the game or encountering something new in real life (recently, a beehive at a botanical garden) that then provides some inspiration for an ongoing campaign. Since that just tends to happen automatically, I don’t really include it above.

Case Study 1: The Bloom One-Shot

The Bloom is a horror module for Liminal Horror. I had picked it up from Spear Witch or Exalted Funeral or somewhere else I forget, and it seemed cool so I signed up to run it at a local con.

The days before my session were packed, so I didn’t have time to fully read the module until the night before. It’s fairly dense, so that took me around half and hour of just flipping back between pages.

When that was finished, there were some problems I had to deal with:

- Even though it’s horror, The Bloom is not a traditional module in that it doesn’t give a clear answer for a lot of the reasons why things are happening.

- I needed to fit the session in a 3 hour timeframe, when it’s designed for more like 3-4 sessions.

The first problem was bit more challenging. For example, various rumors in the book point towards a disaster at a local farm last year, but the farm itself doesn’t explain the full history or origin of the disaster. Because I like to know the answer to those questions in advance, I wrote up a two-word explanation (“contaminated blueberries”) that would give me something to riff off of later.

Finally, I wanted some hook that made it personal for one of the PCs. So, rather than come up with this myself, in the session, after character creation, I asked one of the players to volunteer to have it be a “personal” mission for them. After a player volunteered, I asked them to describe a person who was close to their character, who then became the focus for one of the missing campers.

To solve the second problem, I needed a way to make the session go a lot faster. I also wanted to keep in character creation, since in Liminal Horror it’s fast and also one of the funner parts of the game.

The module recommended one option as starting them at the campsite looking for missing campers, with a monster lurking in the distance. This seemed like a good hook, so I read through that campsite entry again more carefully, and also came up with a reason that the campers might have gone missing (again, not fully explained in the module).

I liked the idea that the campers were poets, since it reminded me of some undergrad camping trips I went on. Because I wanted some form of a handout (since handouts are fun), I hand copied some parts of Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Poem that Took the Place of a Mountain” on to a note that I could insert when it felt appropriate.

Finally, to restrict the session time, I used the module’s implementation of the Doom Die and started it at Doom 2 of 6. I also made this a player-facing mechanic, explaining that the game would end when it was at 6. This helped keep pressure on the players to keep the action moving forward.

In total, it was about 90 minutes of prep the night before, and a 30min refresh before the session the next day. That’s longer than I aim for, but probably makes sense given that it was for a con and for game system that I’m not super experienced with. Overall the game was fun. Despite having 6 players, we were able to reach the “end” of the module and do a short epilogue before the end of time.

Case Study 2: Arden Vul Megadungeon

Arden Vul is a very large megadungeon, running about 1100 pages in total for the module. I had come across this through seeing actual play reports from 3d6 Down the Line and then later on by Eric Vulgaris.

I’ve ran this dungeon across two separate campaigns. The first one started in 2024, and went about 15 sessions or so before I took a break from GMing to focus on some wargaming stuff. I didn’t want to read too much, so I explicitly advertised the game with the cautionary warning that I’d be reading a lot of stuff on the fly and then we may need some pauses for me to look things up.

Before running the first session, I read the initial chapter, some of the faction entries, and then skimmed some of the keys for level 3 and the city ruins on the top. I probably spent about 3-4 hours on this in total.

When the game started, this was more than enough to get going. Each time between sessions, I would spend about 30 minutes looking at some of the areas surrounding where they had last explored, or looking up faction entries that become more relevant as they got deeper. I also took a small amount of time to think about how things might have changed from last session.

After starting the campaign up again at the start of this year (now 17 sessions in), this formula has mostly worked well. As things have come up in play, I’ve developed some additional house rules for scroll scribing and Thoth-induced terror.

Most of my time prepping lately has been in thinking about how different factions are reacting to the ongoing activities. For example, the players (largely through the help of rival adventuring group) kicked out the halflings from their area in level 3, leaving a power vacuum that needed to be filled somehow. Two sessions ago, they left open a door to the catacombs, meaning that undead were no roaming around in new areas, so I adjusted the encounter die to have a 2 indicate a specific catacomb encounter (if in the relevant area), making encounters more likely.

I’m still maintaining what I take to be a decent ratio, usually about 30 minutes of active prep for a 3 hour session.

How I Prep Non-Modules

Since transitioning from 5e, I’ve mostly been a module-based GM when doing OSR stuff. However, there have been a few cases where I’ve been coming up with more of my own content:

- Running Castle Xyntillan back in 2020, a game which transitioned later into a hexcrawl of the surrounding area

- the current Northern Strata campaign on the Purple Server Discord, aiming to playtest material for the Antarctic Adventure Jam

I have less to say here, since most of my prep revolves around trying to write content that resembles a module. That means it’s much more time intensive and somewhat of its own distinct thing from even prepping a campaign.

That said, one of the main things that is useful is coming up with tables to fall back on. For character creation, I wanted to give players some prompts that would give them an initial hook but also help link into the vibe of the setting a bit. So, for example, I have Fighters roll on the following table to determine why they took up arms.

| d20 | Why did I take up arms? |

|---|---|

| 1 | Because the sword is the seed from which all motion flows |

| 2 | To flee the geometer lords |

| 3 | To rage against hierarchical regimes |

| 4 | To combat the mumblings and deceivings of scholars |

| 5 | Because it was commanded in a dream |

| 6 | As preparation for the end times |

| 7 | To sing the glory of nomadic waves |

| 8 | To make audible the nonsonorous forces of the cosmos |

| 9 | As a childhood oath to the werewolves |

| 10 | To light a fire upon the Earth |

| 11 | To hunt the wild beasts at the edges of the Earth |

| 12 | To become a beetle or dog |

| 13 | To translate the violence of crustaceans into new forms |

| 14 | Because the secrets of irrational numbers must stay hidden |

| 15 | To murder all ants |

| 16 | To bring about the asignifying rupture of the court of reason |

| 17 | To write a poem of rhizomatic violence |

| 18 | To champion the existence of empty spaces |

| 19 | As a family tradition to wield your grandmother’s cane |

| 20 | To protect against the alien invaders |

You can see the original versions of the tables here:

In addition, following a guide from Eric Vulgaris on Fever Swamp which I highly recommend, I also come up with Ref-facing tables for sounds, smells, and interesting details that I could use to generate things on the fly.

An example generator (using Perchance) can be found below:

This provides a useful template to riff off of in cases where I don’t have something specifically prepared.

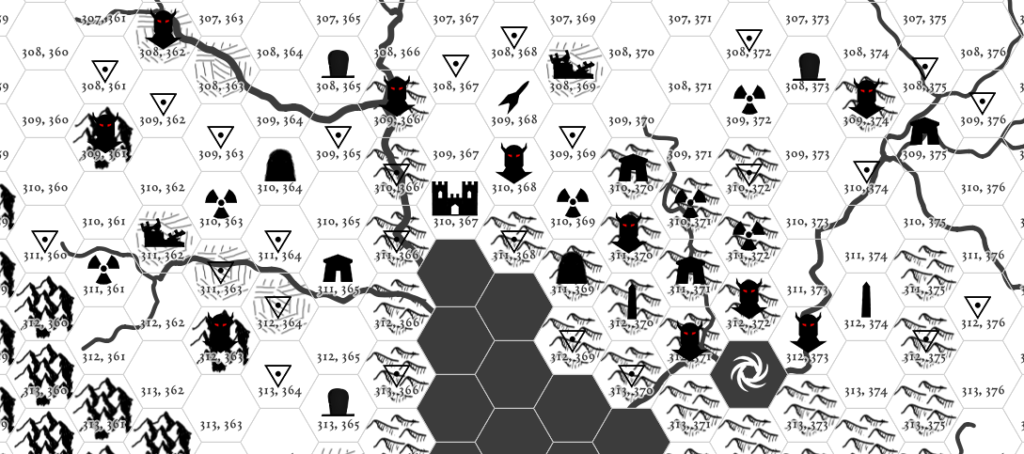

The map in this case was less work, as it was mostly a question of picking a section from the antarctic hexcrawl and placing the settlements. In the current version of the map below (which was finished after about 7 sessions in), I’ve keyed about 60 entries.

Finally, I needed some dungeon. I’m not great at drawing and have been more interested in B2 lately after rereading it, so I ended up using that as a template. I made a new version of the map in dungeon scrawl, and then came up with a short list of ideas of how I wanted to change it which I’ve posted about here:

Addendum: Techniques for Running With Low Prep

Finally, I wanted to provide some tools that are useful for low-prep games. It’s one thing to say “improv more” or “prep less,” but that’s often not very helpful in practice.

Some things that I’ve found useful when hitting the wall of the unknown are:

- Ask clarifying questions – Rather than coming up with something on the spot, stop to clarify how or why the action is being taken. For example, the Thief has asked about whether there are any good areas to rob in town, but you haven’t specifically prepared the treasure in each building. If you ask how she aims to get the information (asking people, looking around) and what she’s aiming to do (steal it, take inventory for later, determine who has power), this can help frame your response and suggest some details you hadn’t thought of otherwise.

- Take a pause – Stop to think for a bit before giving an answer. I play in a public Call of Cthulhu game, and one of the things the GM does really well is to pause at certain moments to think of how a character might respond. In the past, I’ve always felt like I had to have the answer immediately, but this is a nice chance of pace because it allows you to take a breath and reflect on how the situation may be changed by a particular PC action.

- Run at least one game without prep – Once I had run a couple no-prep storygames, it felt a lot easier to improv stuff. It’s easiest to do this as a one-shot without prepping anything beyond reading the game rules–you can make that explicit to the players and help ask prompts about their characters, that you then use as a base to riff off of. I did this with Dungeon World (wouldn’t recommend it), but it could be any system or even ones that are specifically designed for no prep. Once I had run a few games, I felt much more comfortable shifting back into improv mode in cases where my prep ran out.

- Fall back on generators from or procedures from your system of choice – Most games will provide some stocking procedures that you can rely on in a pinch. For example, OSE provides tables that can be used to stock dungeon rooms on the fly. Not every dungeon room needs to have some creative OSR puzzle-style challenge—most of the time, a monster of some sort is more than enough to work with.

- Let the players fill in setting details – If you have a player that’s a goblin, and they ask you what goblins are like in your setting and you don’t have any specific ideas, it’s okay to ask the player if they have any ideas or anything they want to contribute. While it’s definitely not for everyone, in my experience is that more often than not people are happy to come up with something and will sometimes become more enthusiastic about this new lore than something you had come up with yourself.

- Use a random word generator – Doesn’t really matter which one, although this is one I tend to rely on the most. When I truly am out of ideas and want some kind of prompt, I set it to 3 words of any type and then cycle through until something springs to mind that would work. It usually creates weird results, which is a bonus, as players will help you connect things and find logical reasoning between stuff that doesn’t immediately seem to add up. As an alternative to a website, you can have a nearby book (ideally a non-RPG one) and flip to a random page, scanning for words to use as inspiration.

- Offload prep to the players – I force players to take notes a few years ago, which saves a significant amount of time between sessions, which I then make publicly available as a google doc. I usually try to have them track their party items, character specific advancements or downtime, and other statuses that are affecting them. When players take their own notes, they can often remember much better than me what’s happened in past sessions and can help correct me in cases where I’ve forgotten something. Although I only started doing it recently, I’ll also try to ask about what people plan to do next session. This is usually less about prep, though, than it is about trying to reduce the amount of time it takes at the start of session for them to form a plan.

That sums up most of my process. If there’s an overall point, I suppose it’s that, unless you’re looking to perhaps publish something, the most important thing is to play games rather than focus on the peripheral parts. Prep is great as long as it’s something you enjoy, but it shouldn’t be the obstacle to playing and probably any method of prep will work just about as well as any other method.

- See this Pleasures of the OSR post for some reasons why. ↩︎